This article explains the detection engineering process using the YARA tool within the context of malware analysis. It provides an overview of YARA syntax, use cases, and practical examples. By the end of the article, readers will understand how to effectively apply YARA to investigate, identify, and classify malware in real-world scenarios.

In today’s cyberthreat landscape, malware analysis is an essential aspect of the specialized discipline known as detection engineering. Detection engineering refers to a systematic set of processes that facilitate the identification of potential threats within an environment. These processes span the full lifecycle of detection, including gathering detection requirements, aggregating system telemetry, implementing and maintaining detection logic, and validating the effectiveness of the program. Within this context, malware analysis plays a crucial role.

Malware analysis is a complex task that requires various techniques, tools, and a persistent approach to address different scenarios that may arise during the analysis. Among the tools available, YARA stands out as a highly valuable resource for malware analysts and threat hunters. It is a multi-platform program compatible with Microsoft Windows, macOS, and various Linux distributions.

YARA employs a rule-based methodology that allows users to identify and classify malware samples by creating rules that match specific patterns. These patterns can be defined using strings or binary sequences, with the rules incorporating Boolean expressions to determine matches.

Installing YARA is a straightforward process. For Microsoft Windows, begin by visiting the VirusTotal GitHub repository and downloading the latest release binaries (https://github.com/VirusTotal/yara/releases). Once downloaded, extract the contents to a folder of your choice. To ensure YARA is globally accessible on all systems, it is essential to add its folder to the system’s PATH environment variable. You can do this by adjusting the environment variables in the system properties.

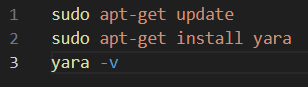

For Linux distributions, start by updating your system, and then install YARA using the default command “apt-get install yara”. After the installation is complete, verify that YARA was installed successfully by running it with the “-v” switch, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Linux Commands for Installing YARA

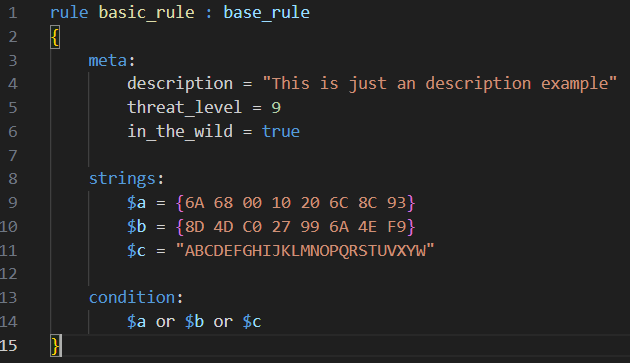

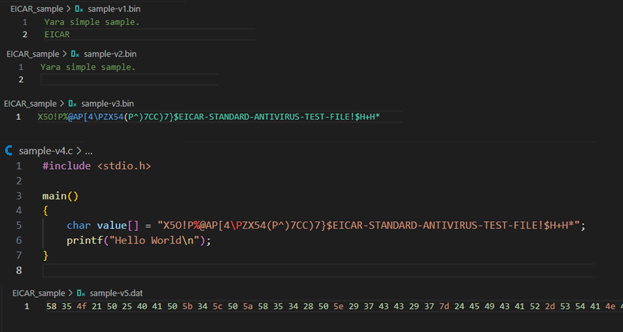

A YARA rule begins with the keyword rule, followed by a unique rule identifier that names the rule. An optional case is using the colon (:) and a tag, as shown in line 1 of Figure 2. This is an interesting option because it is used to classify the rule and the tag it belongs to; in this case, the rule basic_rule belongs to the tag base_rule. This is only a question of semantics, useful for a better understanding of the rules. The rule identifiers are case-sensitive and cannot exceed 128 characters.

Each rule is composed of three sections: meta (optional), strings, and condition. The meta section is used to provide descriptions of the rule, such as annotations and additional information. The strings section defines the patterns we want to identify during analysis. It is possible to create variables using the special character $; these variables can contain strings, hexadecimal values, or regular expressions, and are referenced in the condition section below. This section can be omitted if the rule does not rely on any strings. Finally, the condition section is mandatory and contains the core logic of the YARA rule. This section specifies the condition that determines whether the rule matches a file.

Figure 2: The Basic Structure of a YARA Rule

The power of a YARA rule lies in how versatile its matching possibilities are when analyzing a sample. The list below includes some important options available for these matches:

- Boolean variables

strings:

$a = “text1”

$b = “text2”

$c = “text3”

$d = “text4”

condition:

($a or $b) and ($c or $d)

- ASCII and wide form

strings:

$wide_and_ascii_string = “Microsoft” wide ascii

condition:

$wide_and_ascii_string

- Bytes unknown

strings:

$hex_string = { E2 34 ?? C8 A? FB }

condition:

$hex_string

- Chunks of variable content and length

strings:

$hex_string = { F4 23 [4-6] 62 B4 }

condition:

$hex_string

// Matches:

// F4 23 01 02 03 04 62 B4

// F4 23 00 00 00 00 00 62 B4

// F4 23 15 82 A3 04 45 22 62 B4

- Fixed offset in the file or virtual address

strings:

$a = “dummy1”

$b = “dummy2”

condition:

$a in (0..100) and $b in (100..filesize)

- File size

condition:

filesize > 200KB

- Executable entry point

strings:

$a = { E8 00 00 00 00 }

condition:

$a at entrypoint

- All the strings in one rule

$b = “dummy2”

$c = “dummy3”

condition:

1 of them // equivalent to 1 of ($*)

// all of them -> all strings in the rule

// any of them -> any string in the rule

// all of ($a*) -> all strings whose identifier starts by $a

// any of ($a, $b, $c) -> any of $a, $b, or $c

// 1 of ($*) -> same as “any of them”

// none of ($b*) -> zero matches from strings starting with $b

In our first sample, we will use a practical example involving the EICAR or EICAR Anti-Virus Test File.

As described by the European Institute for Computer Anti-Virus Research (EICAR), the EICAR test file is a safe, standardized file developed by the EICAR in collaboration with the Computer Antivirus Research Organization (CARO). It is designed to test the functionality and response of antivirus software without using actual malicious code, thereby eliminating the risk of causing real harm to systems.

This test file is intentionally short and composed entirely of printable ASCII characters, making it easy to create using any standard text editor. Antivirus programs that recognize the EICAR test file should detect it in any file that begins with the following 68-character string, which must also match the exact length of 68 bytes: X5O!P%@AP[4\PZX54(P^)7CC)7}$EICAR-STANDARD-ANTIVIRUS-TEST-FILE!$H+H*

This string may optionally be followed by whitespace characters (such as space, tab, LF, CR, or CTRL-Z), as long as the total file size does not exceed 128 characters. To ensure compatibility, the string uses only uppercase letters, numbers, and punctuation, and includes no spaces. A common point of confusion is the third character, which is a capital letter ‘O’, not the digit zero.

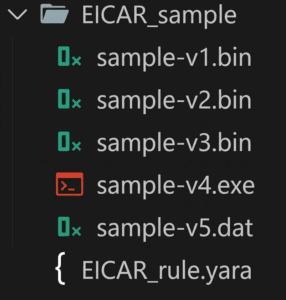

In Figure 3, we have the folder EICAR_sample, with five samples involving the EICAR test file, and outside this folder, a YARA rule called EICAR_rule.yara. Figure 4 shows the content of the YARA rule used in this sample. The title of the rule must reflect what this rule is looking for. Then, there is the meta section, which includes a description of the rule. In the strings section, there are the variables with the patterns that we want to search for in the files that would be used in our analysis. The samples are in text and hexadecimal formats.

Figure 3 : EICAR Sample Files

In this case, we are looking for the string “EICAR“, the full text of the EICAR test file, and its hexadecimal pattern. In hexadecimal format, question marks (?) are used as wildcards to represent unknown bytes. These placeholders can match any byte value during pattern matching. Finally, in the condition section, there is a logical proposition to determine the match of our rule. For this example, we are using the condition any of them, which means the rule will match if any of the values of these variables are present in the files being analyzed.

Figure 4: YARA Rule Searching for the EICAR String Pattern

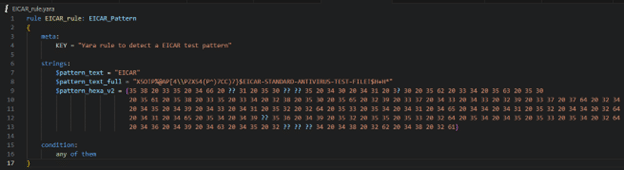

Figure 5 shows the content of the files used in the example. In sample one, there are two lines with strings, and the last line contains the string EICAR. In the second sample, there is only one string and no EICAR string. The third sample has only one line with the EICAR test string. The fourth sample is an executable file; its source code shows that the EICAR string test is present. Finally, the fifth sample is the hexadecimal representation of the EICAR test file format. With this sample, it is possible to verify the strength and flexibility of the YARA rules.

Figure 5: YARA Rule Searching for the EICAR String Pattern

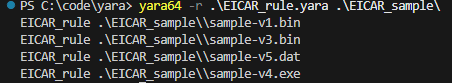

Figure 6 shows the result of running YARA. In this example, YARA is run from a Microsoft Windows 11 machine. The YARA executable is in the PATH environment. In the figure, it is possible to check the switch “-r”, which means recursion, followed by a YARA rule file and the folder containing the files to be scanned. The result shows that our rule matches four files. The sample-v2 was the only one that didn’t have any pattern related to the EICAR test.

Figure 6: YARA result

In our next example, we will use one essential tool to help in the malware analysis process, Malcat. Malcat is an invaluable tool for inspecting a binary because it has a powerful, feature-rich hexadecimal editor combined with a disassembler for Microsoft Windows and Linux. It is ready to examine more than 50 different types of binary files and has a fantastic capture of YARA signatures.

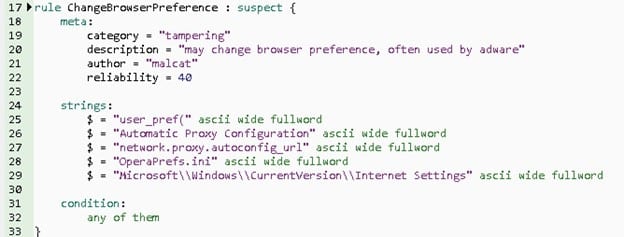

Figure 7 shows a specific rule about a sample that has the capability to change browser preferences. In this case, we have a YARA rule that can match some characteristics that enable the change of some configuration in the browser. The rule starts with a meaningful name and a classification of this rule into the suspect group. In the meta section, there is a clear description of the objective of the rule. In the strings section, we have possibilities related to a program that can change something in the web browser. Finally, the condition section’s logic specifies that if any of these options are present in the sample being analyzed, this sample is suspected of trying to change the browser preference. This rule is very simple but powerful.

Figure 7: The Rule Description to Change Browser Preferences

In real-world malware analysis, it’s common to establish a detection pipeline that includes a workflow for YARA signatures. This detection pipeline helps optimize and automate the processes involved in creating, testing, and deploying detection mechanisms, incorporating capabilities from various teams without requiring manual quality checks from the detection team. The YARA signatures, once deployed within the detection pipeline, are intended to identify malicious executables, malware behaviors, functionalities, and potentially harmful activities. Initially, the detection pipeline is triggered by an event generated by the parent pipeline. New signatures are evaluated based on a tag maintained by the malware analysis team or against a whitelist upheld by the detection team, indicating their readiness for use in detection efforts.

In summary, this article highlights important points about YARA, the structure of a rule, how to install YARA using Microsoft Windows or any Linux distribution, the different kinds of patterns we can utilize—such as text or hexadecimal formats, and applications of this tool with real-world examples. Finally, we saw how a detection pipeline works with YARA signatures.

Cybersecurity Tips

- Understand that YARA is a great tool for detecting patterns in malware analysis and threat hunting.

- Start reviewing the diversity of switches that can be used with the rules.

- Create your samples and experiment with variables and conditions in the rules.

- Understand how YARA rules are created and used in the detection pipeline.

References

EICAR. (n.d.). Anti-malware testfile. https://www.eicar.org/download-anti-malware-testfile/

About the Author

Marcelo Diniz

Marcelo Diniz is a security researcher and senior software engineer with expertise spanning several areas, including security research, vulnerability assessment, reverse engineering, malware research and analysis, digital forensics, threat detection engineering, threat hunting, cyber intelligence, and penetration testing. He is currently employed at Netskope within the malware detection efficacy team, which is part of the Netskope Threat Research division. His responsibilities encompass developing the malware detection engine, conducting meticulous malware analysis, performing advanced reverse engineering, and designing and creating high-quality signatures and detection rules for mechanisms aimed at identifying malware and advanced threats.