AI Program Management vs. Traditional Program Management: Skills That Matter Now

- Ethical Hacking

Framing the Shift

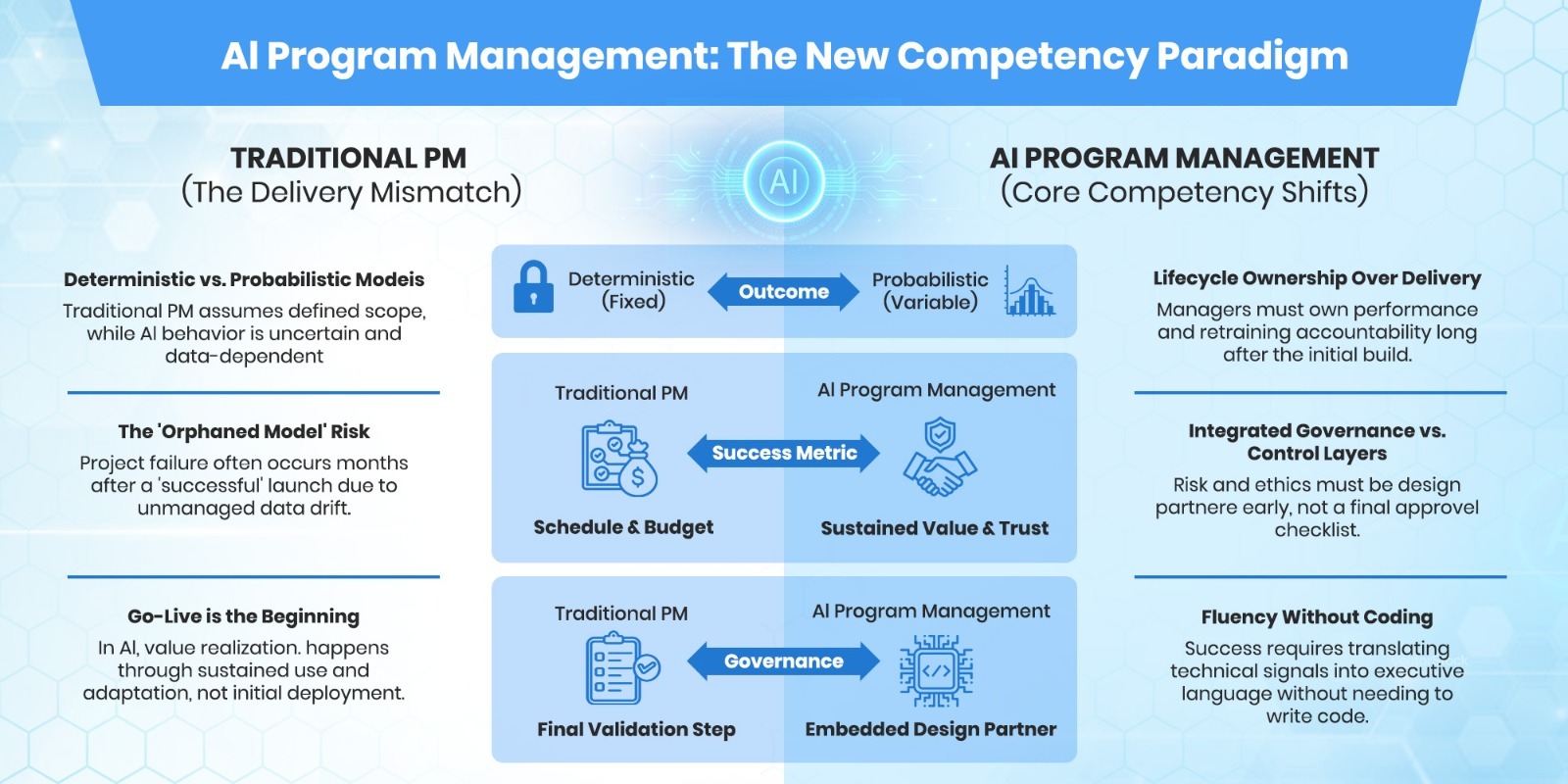

Many organizations assume that strong traditional project managers can naturally step into artificial intelligence (AI) program leadership. The logic feels sound. Planning, execution discipline, stakeholder management, and risk tracking have worked for decades. Why would AI be different?

In practice, this assumption is one of the quiet reasons enterprise AI efforts stall.

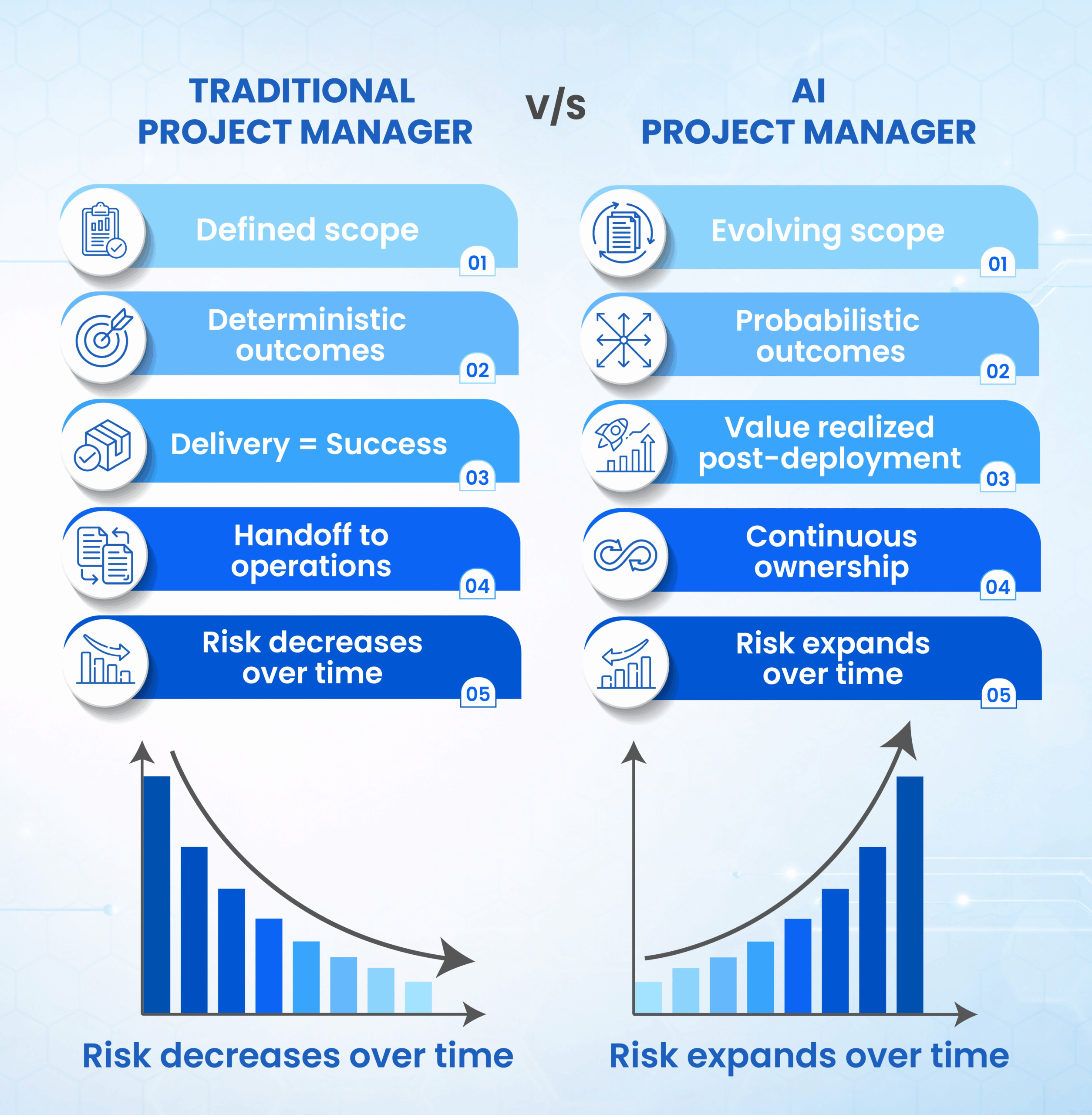

AI programs do not behave like software delivery projects. They do not move cleanly from requirements to build to deploy to closure. They operate continuously. They evolve after launch. Their performance degrades if left unmanaged. Their risks expand rather than shrink over time.

This is not a failure of project managers. It is a mismatch between the delivery model they were trained for and the system they are now being asked to manage.

The difference between traditional program management (PM) and AI program management is not methodology. It is mindset, accountability scope, and decision posture. That distinction sits at the core of the competency model for EC-Council’s Certified AI Program Manager (CAIPM), even when it is not labeled explicitly.

Why Traditional PM Models Fall Short for AI

Traditional project management assumes three stabilizing forces:

- Scope can be defined.

- Outcomes are deterministic.

- Delivery completion signals value realization.

AI violates all three.

Model behavior is probabilistic. Data quality changes over time. Business value emerges through sustained use, not deployment. A project can be delivered perfectly and still fail operationally within months.

A common enterprise pattern illustrates this gap.

A predictive model is delivered on schedule and within budget. Initial results are positive. Six months later, performance declines. No one owns retraining. Data sources have shifted. Users lose trust. The system is quietly bypassed.

From a project perspective, the work was complete. From a program perspective, it never truly began.

AI program management requires ownership across uncertainty, lifecycle, and risk. That is not a natural extension of traditional PM practice. It is a different role.

Skill Shift 1: Managing Uncertainty, Not Just Scope

Traditional program managers are trained to reduce uncertainty through definition. They lock scope, confirm requirements, and control change.

AI introduces irreducible uncertainty.

Model outputs vary. Accuracy can fluctuate. Edge cases surface later. Performance cannot be fully specified up front. The program manager must operate comfortably without guarantees.

In one enterprise AI initiative, leadership demanded a fixed accuracy target before funding at scale. The team complied on paper. Once deployed, real-world data exposed variance that no model tuning could fully eliminate. Trust eroded. The initiative stalled, not because the model failed, but because expectations were mismanaged.

AI program managers manage expectation bands rather than fixed promises. They frame outcomes probabilistically. They design decision checkpoints instead of rigid gates.

This maps directly to CAIPM’s emphasis on decision-making under uncertainty and adaptive planning. The skill is not prediction. It is an informed judgment.

Skill Shift 2: Lifecycle Ownership Over Delivery Ownership

In traditional PM, success is measured at handoff. You reach go-live, close out, and transition to operations.

In AI, go-live is the most fragile moment.

Models begin to drift immediately. Data pipelines encounter edge cases. User behavior changes outcomes. Regulatory interpretation evolves. Without clear lifecycle ownership, systems decay silently.

A recurring enterprise pattern is the orphaned model. Delivered by one team. Operated by no one. Questioned by everyone.

The failure typically unfolds in predictable stages. Initial deployment succeeds. Performance metrics meet baseline expectations. The project team disbands. Monitoring becomes informal.

Further, small degradations accumulate unnoticed. By the time stakeholders raise concerns, remediation costs exceed the original build budget.

AI program managers own outcomes across building, running, monitoring, adapting, and retiring systems. They do not disappear after deployment. They define who is accountable six, 12, and 24 months later.

Operationally, this means establishing clear answers to specific questions before go-live. Who receives performance alerts? Who authorizes retraining? Who funds ongoing data quality work?

Who decides when to retire the system? These are not operational details. They are strategic accountability decisions.

CAIPM frames this as lifecycle accountability. Not as an abstract concept, but as a concrete operating expectation. Someone owns performance. Someone owns risk. Someone owns change.

The best program managers treat deployment as the beginning of value delivery, not the end of project responsibility.

Skill Shift 3: Understanding Models Without Building Them

AI program managers do not need to write code. They do need fluency.

They must understand what drives model performance, what degrades it, what data dependencies exist, and which questions expose risk early.

In one large organization, a program manager assumed that declining accuracy was a model issue. Weeks were spent tuning algorithms. The real problem was upstream data labeling drift caused by a process change in another department.

Without data fluency, the wrong problems get escalated. The wrong teams get blamed. Budgets get wasted.

Effective AI program managers translate technical signals into executive language. They ask precise questions. They challenge assumptions intelligently. They do not delegate understanding.

This aligns directly with CAIPM’s expectation that program leaders can bridge technical, business, and risk domains without becoming engineers themselves.

Skill Shift 4: Integrated Governance and Risk Leadership

Traditional PM treats governance as a control layer. This includes reviews, approvals, and checklists.

AI requires governance to be embedded.

This includes regulatory exposure, ethical considerations, model explainability, data privacy, and operational resilience. These risks intersect continuously with delivery decisions.

An enterprise example illustrates the cost of separation.

A model was deployed to automate customer prioritization. Months later, an audit revealed insufficient documentation of explainability. The system was paused. Rework followed. Budgets doubled. Delivery credibility suffered.

The failure was not governance rigor. It was timing.

The governance function had been engaged late, treated as a final validation step rather than a design partner. Critical questions about model interpretability, decision appeals, and bias testing were raised after architecture decisions had been locked. Remediation required fundamental redesign.

Program managers who integrate governance early ask different questions at different stages. During scoping, they confirm regulatory boundaries and explainability requirements. During design, they validate that technical choices support auditability. During testing, they ensure bias and fairness metrics are tracked alongside performance metrics. During deployment, they confirm documentation meets compliance standards.

This is not governance theater. It is risk-informed delivery.

CAIPM treats governance not as oversight theater, but as a core leadership competency. Program managers are expected to orchestrate it, not react to it.

Organizations that separate delivery and governance accountability create expensive rework loops. Those that integrate them build trust faster and scale more confidently.

Skill Shift 5: Cross-Functional Orchestration at Scale

Traditional projects are cross-functional. AI programs live inside them.

Data, technology, legal, risk, security, operations, procurement, and business owners all influence outcomes. No single function can succeed alone.

A common failure pattern is accountability diffusion. Everyone contributes. No one owns it.

AI program managers operate as integrators. They resolve tension between speed and safety.

They align incentives. They surface conflicts early.

This orchestration role is central to CAIPM’s program-level orientation. AI success is rarely blocked by algorithms. It is blocked by coordination failure.

Skill Shift 6: Measuring Value Beyond Schedule and Budget

Traditional PM success metrics are necessary. They are not sufficient.

AI value must be measured through sustained performance, adoption, trust, and risk containment. These indicators change over time.

One organization celebrated cost savings from an AI automation. Within a year, manual overrides increased. Adoption dropped. The system technically existed, but business value had eroded.

AI program managers track leading and lagging indicators. They know when to double down, pivot, or retire systems. They treat stopping as a leadership decision, not a failure.

CAIPM reinforces this through outcome-oriented measurement rather than delivery optics.

What Traditional PM Skills Still Matter

None of this diminishes the value of traditional PM skills.

Execution discipline still matters. Communication still matters. Risk visibility still matters.

What changes is where those skills are applied. Less focus on task completion. More focus on decision quality. Less emphasis on closure. More emphasis on continuity.

The best AI program managers are often strong traditional program managers who have expanded their accountability horizon.

Implications for Organizations and Talent

Organizations that treat AI program management as a minor extension of traditional PM roles struggle longer than necessary. Those that invest in distinct competencies build resilience faster.

Hiring and Development Strategy

The talent question is not binary. Organizations do not need to choose between developing existing PMs or hiring new talent. They need both pathways.

Strong traditional PMs with curiosity about uncertainty, comfort with ambiguity, and appetite for continuous accountability can transition effectively. They need structured exposure to AI lifecycle realities, governance integration, and probabilistic thinking. Rotation programs that pair PMs with technical teams during model development accelerate this learning.

However, not all traditional PMs will transition successfully. Some excel in defined-scope environments and struggle when outcomes remain fluid. Forcing the transition creates frustration and program risk.

Organizations also benefit from hiring program managers with direct AI delivery experience, even if that experience comes from smaller-scale efforts. These individuals bring pattern recognition that cannot be taught quickly.

The filtering question is simple: Can this person operate effectively when the success criteria evolve after launch? If the answer is unclear, the role is likely a mismatch.

Organizational Structure

AI program management fails when positioned as a coordination role without authority.

Effective structures grant program managers clear accountability for outcomes, budget influence, and escalation pathways that bypass functional silos. They report to leaders who understand that AI programs require different success measures than traditional projects.

Organizations that embed AI program managers within business units often see faster adoption and clearer value realization. Those that centralize them within information technology (IT) or innovation functions risk creating delivery engines disconnected from operational reality.

Structure also determines whether lifecycle accountability is real or rhetorical. If program managers lose budget authority after deployment, lifecycle ownership becomes impossible.

Competency Frameworks and Assessment

CAIPM’s exam blueprint and competency framework address this gap directly by organizing expectations across six domains: Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, AI Operations and Data Management, AI Adoption Leadership, Intelligent Automation and Prompt Engineering, AI Security, and AI Applications and Future Trends.

Organizations using CAIPM as a baseline can assess current capability, identify development needs, and build role definitions that reflect actual program requirements rather than traditional PM templates.

Certification provides a shared vocabulary. It does not replace experience, but it establishes a credible threshold for program-level accountability.

Looking to the Future

AI programs test organizational maturity more than technical capability.

The gap between traditional PM and AI program management is not a skills gap in isolation. It is a responsibility gap.

Organizations that close it build a durable advantage. Those that do not repeat the same failures with better tools.

The shift is already underway. The question is whether organizations recognize it in time to invest appropriately.

About the Author

Brian C. Newman

Brian C. Newman is a senior technology and AI program practitioner with more than 30 years of experience leading large-scale transformation across telecommunications, network operations, and emerging technologies. He has held multiple senior leadership roles at Verizon, spanning global network engineering, systems architecture, and operational transformation. Today, he advises enterprises on AI program management, governance, and execution, and has contributed to the design and instruction of EC-Council’s CAIPM and CRAGE programs.