While the cybersecurity industry often caters to large enterprises and national-level mandates, local (state) governments remain underserved despite handling vast amounts of sensitive personal and financial data. This makes them attractive targets of the same cyberthreats facing larger corporations, including ransomware, phishing, insider risks, and IoT vulnerabilities. Explore cybersecurity strategies tailored to local governments, from building compliance-driven policies and adopting zero trust principles to securing supply chains/vendor management and leveraging federal grants and partnerships.

Local Government: A Complex IT and OT Landscape

Local governments operate in one of the most complex technology environments, balancing enterprise IT with operational technology (OT) and Internet of Things (IoT) systems across diverse locations. Enterprise IT supports multiple departments: public safety, libraries, finance, HR, elections, legal, planning, and more. OT/IoT environments span public works functions such as water treatment, power generation, traffic management, and waste management, often involving systems like traffic light controls, webcams, and plant automation. Multiple locations may include office buildings, police and fire stations, water and electric plants, dumps, airports, and ports. The scope of technology use varies by the size of the municipality; cities, counties, and towns may have all, some, or only a subset of these elements. Drawing from several cybersecurity assessments conducted for local governments in Virginia, it’s clear that safeguarding these interconnected systems requires a comprehensive, tailored approach to compliance and cybersecurity.

Where Does IT and Cybersecurity Fit?

In local government, IT and cybersecurity often sit much lower in the organizational hierarchy compared to corporate environments. While a corporation might have a Chief Information Officer (CIO) positioned alongside the CEO, COO, and CFO, local government IT leaders are often buried three levels down, frequently without a dedicated Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) or cybersecurity director.

In most cases, cybersecurity responsibilities fall under the IT department, if they exist at all. This structure limits IT’s influence over governance decisions, even though technology touches every department, from public safety and utilities to administration and community affairs.

For effective governance and cybersecurity programs to succeed, IT leaders must build strong relationships across departments and with deputy managers. Given that IT spans all functional areas, collaboration is essential to ensure data security and maintain strong governance practices.

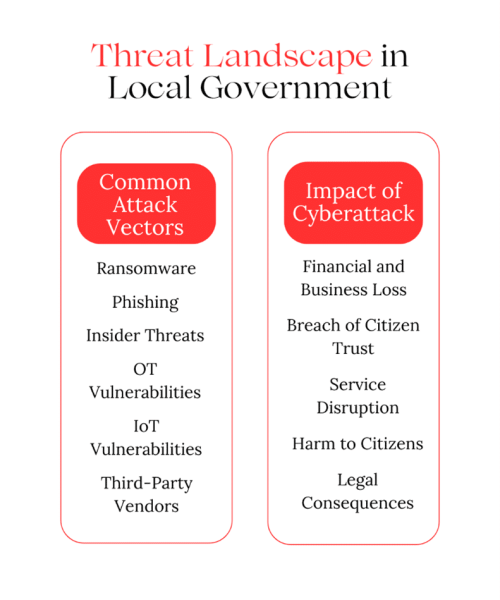

Threat Landscape in Local Government

Local governments face many of the same attack vectors as other organizations: ransomware, phishing, insider threats, OT and IoT vulnerabilities, and risks from third-party vendors through SaaS or cloud services. The difference lies in the impact.

- In the private sector, a cyber incident may cause financial loss, reputational damage, or service downtime, but rarely does it threaten public safety.

- In local government, an attack can disrupt essential services like water, power, waste management, and emergency response.

Such disruptions not only cause financial loss but also erode citizen trust, degrade the quality of life, and in severe cases, endanger lives.

A successful attack could prevent police, fire, or medical services from responding to emergencies or cut off vital utilities, directly affecting a community’s ability to live safely and comfortably.

Regulatory and Compliance Requirements: Limited Enforcement in Local Government

If a cyberattack impacts local government operations, one might assume there are strict regulation and compliance requirements in place. In reality, at least in Virginia, such requirements are minimal and often apply only to specific functions.

Examples of Common Frameworks and Mandates:

- HIPAA: For local health departments handling medical data

- NIST 800-53/800-171: For general cybersecurity controls

- CJIS: For law enforcement agencies accessing Criminal Justice Information Services (audited)

- State-Specific Guidance: E.g., Virginia SEC530 (subset of NIST 800-53)

State agencies may provide security recommendations, but most are suggestions, not mandates. For example, the Virginia Department of Elections requires self-assessments of information security, but only for election-related systems, not other city or county functions.

As a result, many towns, cities, and counties operate without regular audits or enforced compliance, leaving large portions of their IT and OT infrastructure outside the scope of mandatory regulations.

Governance and Risk Management in Local Government

Many local governments lack formal cybersecurity governance structures—with documented plans, policies, and procedures—especially if not legally required. Smaller or less-resourced localities are more likely to have inadequate or incomplete programs. In contrast, larger cities and counties often have more mature governance due to greater funding, staff, and public scrutiny.

Key Elements of Effective Governance:

- Cybersecurity Governance Framework: Plans, policies, and procedures to guide IT and OT security

- Risk Assessments: Asset identification, threat modeling, and a comprehensive vulnerability management program

- Framework Adoption: ISO/IEC, CIS Controls v8.1, or NIST CSF 2.0 as baselines for best practices

- Incident Response Planning: Clear escalation procedures and reporting requirements

Risk Management Practices

A proper risk assessment starts with knowing all assets, not just laptops, servers, and firewalls, but also IoT devices (e.g., traffic cameras, smart cabinets) and OT systems (e.g., water treatment controls). These should be segmented from enterprise networks to reduce risk.

Vulnerability Management Beyond Patching Windows Systems:

- Regular scanning of all devices, including IoT and OT assets

- Identifying unauthorized devices (e.g., personal wearables) on the network

- Addressing configuration weaknesses in addition to missing patches

Frameworks for Implementation

The CIS Controls v8.1 framework is a practical starting point. Its Implementation Group 1 has 56 safeguards that provide baseline cyber hygiene, covering asset management, vulnerability management, employee awareness training, and disaster recovery. Larger or more mature localities can expand to Implementation Groups 2 and 3, or adopt more advanced frameworks.

Other Examples of Advanced Frameworks:

- NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0: Comprehensive guidance for building robust programs

- ISO/IEC: IT governance framework for aligning technology with organizational goals

Incident Response Plan

Local governments in Virginia must report cyber incidents to the State Police. This requirement should be embedded in a formal incident response plan to ensure timely escalation and mitigation. Without these measures, cybersecurity often defaults to ad-hoc practices, leaving critical systems exposed.

Building a Resilient Cybersecurity Program

A strong cybersecurity program relies on layered security: a “defense in depth” approach combining multiple tools, strategies, and policies to protect systems, data, and users.

Layered Security Controls:

- Firewalls and Endpoint Protection: While firewalls remain important, remote and hybrid work mean endpoint protection is now the true front line.

- Identity and Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Protect cloud services (e.g., Microsoft 365, Google Workspace) with strong identity management and MFA.

- Backups: Maintain reliable, tested backups to recover from ransomware or data loss.

Zero Trust and Network Segmentation:

- Zero Trust: Apply zero-trust principles; this requires continuous verification and minimal trust between systems.

- Segmentation: Separate networks by function; avoid flat network designs that allow broad access.

- Micro-Segmentation: Restrict resource access to only necessary devices and users.

- Wireless and Remote Access: Isolate critical systems from wireless networks, use certificate-based authentication or 802.1X, and secure VPNs with MFA and least privilege principles.

Vendor Risk and Supply Chain Security:

- Understand exactly what vendors, especially smaller service providers, are responsible for versus your own responsibilities.

- Ensure contracts include clear security obligations and a right to audit.

- Avoid assumptions about patching or system updates; verify critical systems like 911 dispatch servers are maintained.

Staff Training and Awareness

- Users remain the largest attack surface.

- Conduct regular security awareness training.

- Run frequent phishing simulations to reinforce good practices.

Cyber Insurance

Consider cyber liability insurance to help transfer risk and cover damages or liability in case of a breach, ensuring policy terms align with organizational needs.

Funding and Resource Optimization

Local government cybersecurity funding often comes from tax revenues (e.g., property taxes, service fees for water, electricity, or waste management, etc.). But in most cases, this isn’t enough, leading to a sharp divide between the “haves” and “have-nots.”

A typical mid-sized city or county might have 500 employees but fewer than 10 IT staff, often with no dedicated security role. These small teams juggle everything from help desk support to server administration, network management, and application maintenance. This lean staffing leaves them overstretched and unable to meet growing security demands.

Potential Funding and Optimization Strategies:

- Federal and State Grants: Programs from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial (SLTT) can help cover costs for security tools like EDR solutions or managed security services. In Virginia, local governments must apply through state entities.

- Cooperative Purchasing Agreements: Regional buying groups can pool resources to negotiate better license pricing.

- Cloud-Based Security Services: Reduce infrastructure costs while improving security capabilities.

- Managed Security Service Providers (MSSPs): Outsource cybersecurity functions to MSSPs to gain monitoring, incident response, and specialized expertise.

- Public–Private Partnerships: Leverage organizations like:

- Center for Internet Security (CIS): Free CIS Controls v8.1, security benchmarks, and guidelines

- Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS-ISAC): Low-cost endpoint detection, network monitoring, and actionable threat intelligence for state and local governments

Some smaller towns even outsource their entire IT function to an MSSP, which is common in jurisdictions without critical infrastructure, like water treatment plants or airports, but still responsible for essential services like police, fire, sanitation, and traffic management.

Conclusion

Proactive governance is the foundation of resilience. Local IT leaders must build strong relationships with other department heads, advocate for cybersecurity, and ensure governance extends across both IT and OT/IoT environments. Local government cybersecurity leaders should view compliance as a starting point, applying standards like election security and CJIS across all departments. They should focus on risk-based investments, maintain asset inventory, and address high-risk exposures. They should also aim to reduce human errors through regular security awareness training and foster a security-first culture. Finally, they should maximize available resources such as state and federal funding, cooperative purchasing, MSSPs, and partnerships with CIS and MS-ISAC.

With constrained budgets and limited staff, strategic resource use and strong governance can bridge the gap between minimal compliance and true operational resilience.

Tags

About the Author

Nick Kuriger

Director of Information Technology/Information Security Officer, Virginia State Bar

With over 25 years in IT and cybersecurity, Nick Kuriger serves as the Director of Information Technology and Information Security Officer at the Virginia State Bar. He is also an Associate Professor and conducts cybersecurity assessments for Virginia’s local governments. Kuriger holds 13 EC-Council Certifications, including CCISO and CEH Master, along with over 100 other certifications from (ISC)², ISACA, SANS, Microsoft, AWS and CompTIA. He also holds multiple master’s degrees in IT, cybersecurity, and business and is committed to advancing cybersecurity practices and education through his work.